Genetic fingerprinting reveals secrets of cassava varieties grown in Ghana

Genotypes are mapped against local variety names

Researchers from IITA, Michigan State University and Ghana’s Council for Scientific and Industrial Research – Crops Research Institute (CSIR-CRI) collected more than 900 samples of cassava grown by 495 farming households in Ghana’s top cassava-producing regions, sent them to Cornell University for genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS), and compared their genetic ‘fingerprints’ with those of 64 cassava accessions held at CSIR-CRI (common landraces and released varieties) that were used as a ‘reference library’. The results provide an unequivocal view of the actual varieties being cultivated across Ghana.

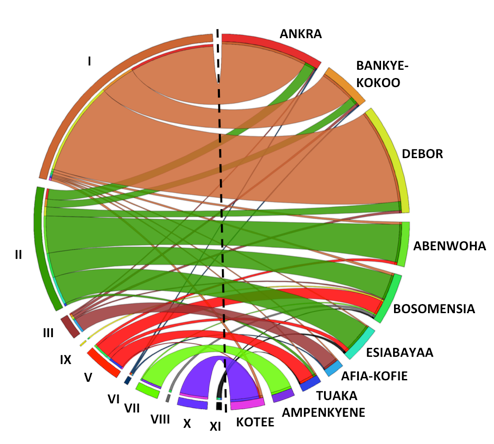

The researchers found that 30% of the cassava collected on the farms matched specific released varieties, which is consistent with the results of a prior impact assessment. However, their analysis revealed widespread discrepancies in the names of varieties and landraces. While the farmers provided 180 different variety names for the 917 cassava accessions collected, genetic analysis revealed that many were actually the same variety, whereas some accessions with the same name were genetically different.

“One of the biggest lessons is that you can’t rely on common names of varieties,” said Ismail Rabbi, a cassava geneticist at IITA who led the study’s DNA fingerprinting component. “You also can’t always rely on morphological characteristics, because these are influenced by environmental conditions and plant growth stages. The methods traditionally used to assess the impact of crop improvement are not as reliable as DNA fingerprinting.”

Genetic analysis showed that 69% of the accessions collected belong to 11 major variety groups, whereas the rest are the result of inter-varietal crosses. Nearly a quarter of the accessions collected were the same landrace, which farmers identified as Ankra, Debor, Bankye Kokoo, etc., whereas approximately 17% belonged to a landrace that was evaluated and released by Ghanaian universities in 2004-2005 as ‘IFAD’ and ‘UCC’. This means that about 40% of Ghanaian farmers grow just two varieties.

“These two varieties are grown all over the place. We should do more research to understand why they are so popular,” Rabbi said. He explained that characterizing the two varieties’ traits could help cassava breeders ensure that improved clones coming out of their breeding pipelines have those traits, and thereby increase farmer uptake.

A comparable but more comprehensive study underway in Nigeria, with support from RTB and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, involved the collection of more than 8,000 cassava samples from 2,500 farms that will be compared to a reference library of nearly 4,000 accessions. The results of this study, to be completed in 2016, will provide a clear picture of the distribution patterns of improved varieties and landraces across Nigeria.

Rabbi observed that genetic fingerprinting can also be used to identify gaps and duplicates in genebanks, in order to make their collections more comprehensive while reducing redundancies. Several of the more common cassava landraces collected in the Ghana study weren’t represented in the reference library, which also included identical accessions with different names. Moreover, genetic analysis revealed that the 64 accessions in that reference library were actually just 34 unique cultivars, 16 of which were released varieties. To avoid such problems, IITA researchers are using GBS to improve the IITA cassava genebank collection.

“Genome-wide genetic markers are useful for a variety of identification applications,” said Rabbi, who explained that the study also provided information on the ancestry of and relations between specific varieties and breeding lines, which can help cassava breeders to better classify their material and identify sources of traits.

He added that such research is only possible thanks to recent advances and reductions in the cost of next-generation sequencing technologies. “This is something that we could not have imagined just a few years ago,” he said.

Related links